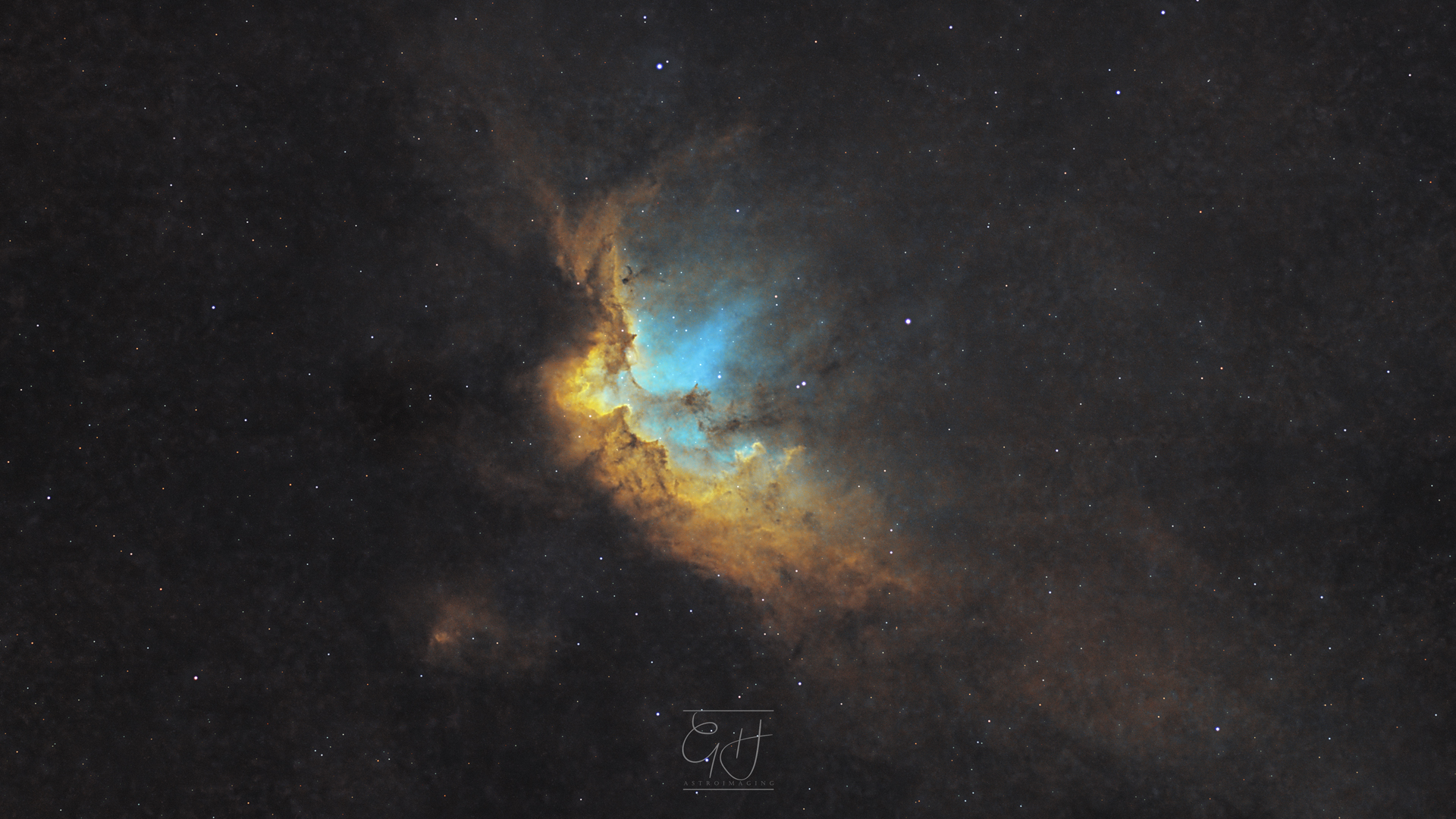

Wizard Nebula, January 1 2025

New Year's Day 2025 brought my first opportunity for many months to get active in astrophotography again. The weather forecast was for clear skies all night, and for once it turned out to be reliable.

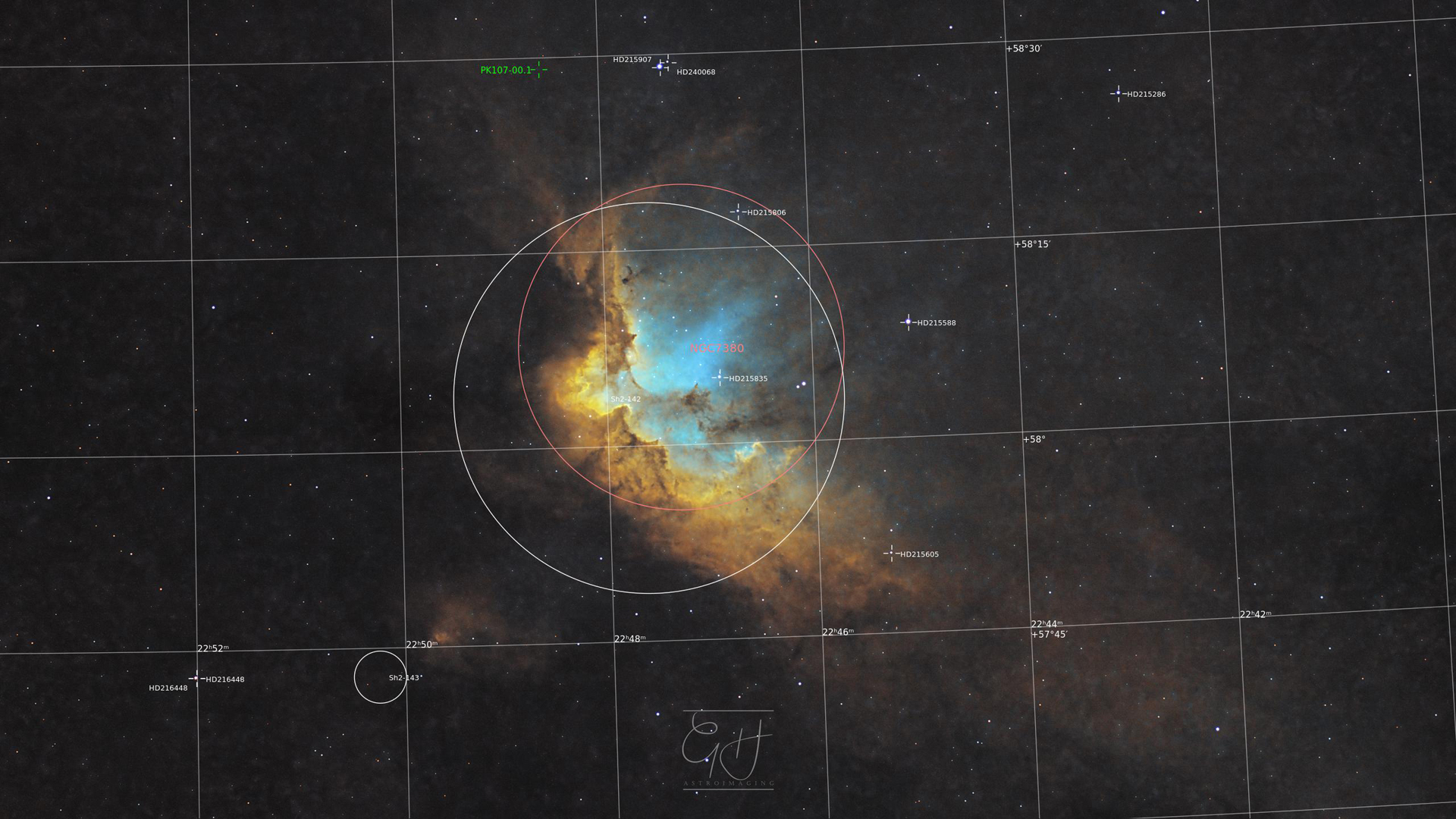

My main difficulty in getting started (after the usual ones of trying to remember how all the gear connects together) was in deciding what target to aim for. Should I be aiming for something I've never imaged before? What was visible without being blocked by my house, or any other surrounding houses? In the end I chose to aim at a target I had imaged before with my Canon 6D to attempt to get a new image based on narrowband emissions for comparison. The target was the Wizard Nebula, also known as Sh2-142. This is an area of emission nebulosity around the open cluster NGC7380, found in the constellation Cepheus. One of my main reasons for choosing this object was the fact that it is circumpolar from my location. What this means is that from my latitude on the planet, this object never sets below the horizon, so I knew I would be able to take advantage of the night-long clear sky to capture as much exposure time as possible.

As with many of my more recent images, this was created by capturing narrow sections of the visible light spectrum associated with the elements sulphur, hydrogen and oxygen, using special filters that only allow certain wavelengths of light to pass. Capturing the data is only the start of the process though, and it takes a great deal of time to subsequently process that data to create images for viewing that aren't simply a black frame with a few isolated dots representing the stars. I have heard a few people say that this data processing step is somehow cheating, and the final image isn't 'real', whatever that means. I suspect that the people who hold this opinion don't actually understand how cameras work, and probably understand even less about how human vision works. The reality is that even when you take a quick snap on your smartphone camera, there is a huge amount of digital processing that takes place without the user's intervention to create a viewable image from the data created by the interaction of photons with the individual photoreceptors on the camera sensor. The difference with astrophotography is that the amount of processing required is significantly greater than with normal daylight photography purely because we try to create differentiation between parts of the image where the differences in brightness are incredibly small, because the entire object is extremely faint.

To create this image, the SII (sulphur) signal is mapped to the red channel, H-alpha (hydrogen) is mapped to green and OIII (oxygen) is mapped to blue, but there is then a lot of colour adjustment made to create the final image because in almost every object in the sky the hydrogen signal is enormously brighter than any others so without the further colour adjustments the final image would simply appear to be green with no other colours really visible. Finally, the data from the red, green and blue filters was combined to give reasonably accurate star colours, which were overlaid on the nebula image.

You can view this image in the WorldWideTelescope by clicking here.

Sign in to enable commenting